Detective Kenny Driscoll: A Legacy of Service, Innovation, and Unwavering Dedication

Introduction

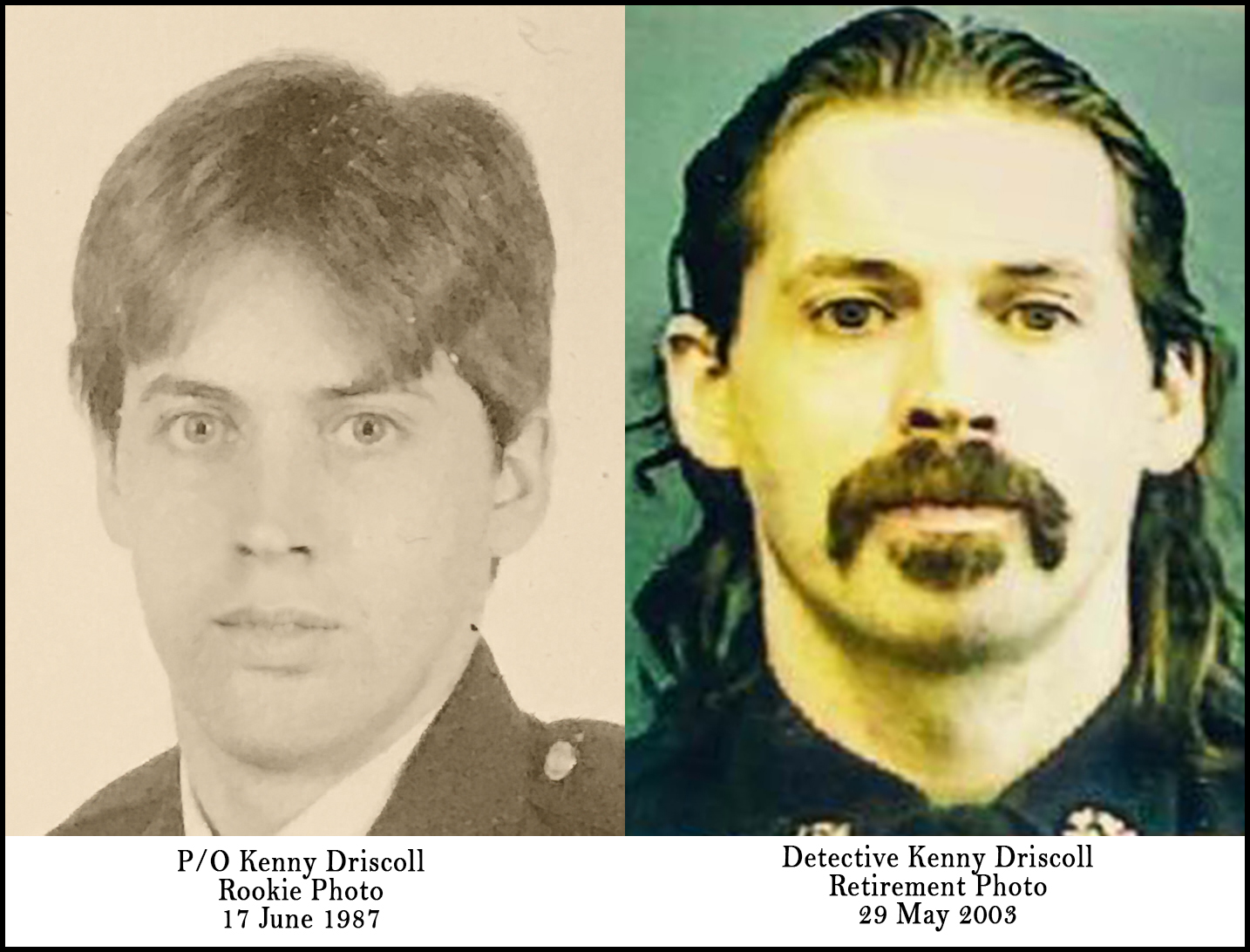

In the storied history of the Baltimore Police Department, few careers shine as brightly as that of retired Detective Kenny Driscoll. Over nearly sixteen years of active service, from June 1987 to May 2003, Driscoll distinguished himself not merely as an exceptional police officer, but as a pioneering investigator whose innovative techniques, relentless dedication to justice, and remarkable courage under fire earned him recognition as one of the most decorated officers in department history.

His story is one of transformation—from a young patrol officer walking the challenging streets of Central District to a master detective whose groundbreaking work with statement analysis revolutionized investigative techniques across multiple law enforcement agencies. Even after a career-ending injury left him paralyzed, Driscoll's commitment to the Baltimore Police Department never wavered. His post-retirement work preserving the department's history and supporting injured officers has cemented his legacy as a true servant of both his fellow officers and the community.

Early Career: Foundation of Excellence (1987-1993)

Joining the Force

Kenny Driscoll's journey into law enforcement began with determination and persistence. In 1986, he was initially hired by the Baltimore County Police but was cut before the class began, becoming one of the alternates. Following his recruiter's advice, he joined the auxiliary police to gain experience and demonstrate his commitment to the profession.

On June 17, 1987, Driscoll was sworn into the Baltimore Police Department. Just three days later, on June 20, 1987, he graduated from the Baltimore County Auxiliary Police Course—a testament to his dedication to comprehensive training. After graduating from the Baltimore Police Academy on December 11, 1987, he was assigned badge number 3232 and posted to Central District Patrol, where he would quickly establish himself as an officer of exceptional merit.

Learning the Streets

Assigned to Central District's Sector 3 (the 136 car covering Whitelock and Brookfield), Driscoll received his practical education from seasoned veterans who would shape his approach to policing. Officers like Joe Stevens, Kenny Byers, Jon Pease, Eddie Coker, Freddy Fitch, Bobby Ackiss, and Terry Caudell provided the real-world training that no academy could replicate.

Between 1987 and 1994, Driscoll partnered with several officers who would become lifelong friends and influence his policing philosophy: Delmar "Sonny" Dickson, Chuck Megibow, George Trainer, John Calpin, Johnny Brandt, and Gary Lapchak. These partnerships, particularly his legendary collaboration with John Calpin, would produce some of the most memorable police work in Central District history. The duo became known for their motto, borrowed from the film Next of Kin: "Together we made a mean pair of two!"

Early Recognition and First Line of Duty Shooting

Driscoll's dedication extended beyond his own jurisdiction from the very beginning. In 1989, the Baltimore County Police awarded him a Commendation Ribbon for his off-duty assistance to the county—an honor the City of Baltimore matched in recognition of his exemplary service and commitment to enhancing the department's reputation through inter-agency cooperation.

The year 1990 marked a pivotal and dangerous moment in Driscoll's young career. He was involved in his first line of duty shooting on Mason Alley, where he used his service revolver, a .38 caliber Smith & Wesson Model 64. The incident, which demonstrated his courage under fire, earned him his first Bronze Star. The following year, in 1991, Driscoll received his first Officer of the Year Award—a distinction he would earn an unprecedented seven times throughout his career, more than any other officer in Baltimore Police Department history.

The Golden Rule: Building Rapport Through Respect

From early in his career, Driscoll operated by a simple but profound philosophy: treat others as you would like to be treated. This approach, rooted in the Golden Rule, set him apart from many officers and would become a hallmark of his investigative success.

Coming from a large family where some relatives had served time while others became police officers, Driscoll learned not to view criminals as lesser than himself. "To him, they were all family," his wife Patricia recalls. This perspective allowed him to see the humanity in those he arrested and to establish connections that often led to confessions and cooperation.

People who were arrested frequently requested to speak with Driscoll specifically. Even after his career-ending injury, suspects asked for him to conduct their interviews. When informed of his injury, some asked officers to call him so they could personally wish him a speedy recovery. Over the years, former arrestees sent him messages thanking him for treating them with respect when others had been less than cordial.

Becoming a Field Training Officer and Second Shooting

In 1992, Driscoll's expertise was formally recognized when he became a Field Training Officer (FTO), entrusted with training the next generation of Baltimore police officers. That same year proved to be one of the most challenging and consequential of his career.

On May 3, 1992, just three days before his youngest daughter was due to be born, Driscoll and his partner John Calpin were working crowd control at Odell's nightclub on North Avenue when a call came in about an armed suspect. What followed was a textbook example of courage, precision, and life-saving decision-making under extreme pressure.

The officers encountered a suspect matching the description—armed with a black semi-automatic pistol and wearing a light blue velour sweatsuit. When confronted, the suspect grabbed his own brother as a human shield and began raising his weapon toward Officer Calpin, who stood exposed with no cover just 8-10 feet away.

Driscoll, positioned approximately 30 feet to the east, faced an impossible shot: a small target partially obscured by an innocent hostage, at a distance beyond his comfort zone, with his partner's life hanging in the balance. He had time for only one shot.

"Ken inhaled deeply, took aim, and then gently squeezed off a single round after carefully aiming," the incident report notes. The bullet struck the suspect in the left side of his chest, traveled downward through his body, and nearly exited near his lower right hip. The single shot ended the threat without harming the hostage.

Driscoll and Calpin immediately advanced on the suspect. While Officer Brian Curran secured the hostage, Driscoll took control of the suspect's weapon, handcuffed him, and began administering first aid for what he recognized as a sucking chest wound. Using a plastic potato chip bag found nearby, he covered the entry wound—a simple but effective technique that doctors later said likely saved the suspect's life.

The incident resulted in a broken and separated right shoulder and clavicle for Driscoll, injuries that would have sidelined many officers permanently. Despite his injuries, 1992 became one of his most decorated years. He received his second Bronze Star, his first Citation of Valor, his second Commendation Ribbon, and was named Central District Officer of the Month in August. He also completed his first LSI-SCAN Course in Scientific Content Analysis and earned recognition for five years of safe driving.

Three days after the shooting, on May 6, 1992, Driscoll's youngest daughter, Patricia Lynn (nicknamed "Tricia" or "Tink"), was born. She would grow up to become a doctor specializing in the treatment of children with autism.

The following year, 1993, brought Driscoll his second Officer of the Year Award and his third Bronze Star, cementing his reputation as one of Baltimore's finest.

The SCAN Revolution: Pioneering Statement Analysis (1993-1994)

Discovering a New Tool

While recovering from his 1992 shoulder surgery—which involved the removal of a large portion of his clavicle and rotator cuff repair—Driscoll attended an in-service class where he was briefly introduced to SCAN (Scientific Content Analysis) by Mike Ryan, a former police officer. The technique, which analyzes speech patterns, manners of expression, and inconsistencies in written statements to detect deception, immediately captured Driscoll's imagination.

There's a saying in law enforcement: "It is just as important to exonerate the innocent as it is to convict the guilty." This principle resonated deeply with Driscoll as he studied the technique during his recovery. The SCAN method was so new and unproven that the Baltimore Police Department refused to pay for training. Undeterred, Driscoll paid for his own training out of pocket, using settlement money from his injury. He purchased all the books, videos, and audio cassettes available, and later paid to attend the live 5-day course in Virginia.

The Breakthrough Case

In 1994, Driscoll transferred from patrol to the Major Crimes Investigative Unit. On his first night back to full duty after nearly three months of recovery, he was asked to interview a suspect in a carjacking case. The suspect had been found behind the wheel of the stolen car, matching the description down to his clothing and shoes. It seemed like an open-and-shut case.

But when Driscoll analyzed the suspect's written statement using the SCAN technique, something didn't add up. He couldn't find the deception indicators he expected to see. After more than a year of study, he was stumped and ready to call his instructor at 3 a.m. Then it hit him: in all his training, they had never studied a truthful statement. What if the suspect was actually innocent?

Driscoll called the reporting person—the alleged victim—into the station and had him write a statement. "Before Ken could turn that paper 180 degrees for him to read it, he had found more than a few red flags," Patricia Driscoll recalls. Within 15 minutes of reading the statement in its entirety, Driscoll had confronted the writer and gained a full confession: the carjacking claim was false.

Driscoll immediately released the arrested suspect without charges, saving him from potentially many months in lockup awaiting trial. The victim admitted that he had not been robbed at an ATM as initially claimed but had instead tried to rip off a drug dealer in the Eastern District and was shot in the process.

Institutional Recognition and Resistance

When Central District's Major Leonard Hamm (who would later become Commissioner Hamm) learned of Driscoll's success in clearing a suspect using this new technique, he was so impressed that he had Driscoll transferred from patrol to the Major Crimes Unit. Major Hamm trusted Driscoll and knew he wasn't trying to sell "junk science" to the department.

However, not everyone was convinced. Some of Driscoll's colleagues dubbed the technique "witchcraft," "chicken bones," or a "SCAM" (a play on SCAN). There was even a sergeant who didn't like the idea of someone being able to find deception without some kind of machine and, for that reason, didn't like Driscoll.

But Driscoll's supervisor, Sergeant Randy Dull, appreciated the new technique and often defended Driscoll when traditionalist brass didn't understand or refused to accept it. Sgt. Dull used Driscoll's impressive statistics to silence the doubters, and Driscoll, grateful for this support, remained loyal to Central's Major Crime Unit even when other units tried to recruit him.

Becoming a Master and Teacher

Driscoll was trained by Avinoam Sapir, the developer of the SCAN technique. After Driscoll uncovered several linguistic traits that held serious meaning and helped solve cases, Sapir called him a "Guru" on the subject. Sgt. Dull observed that "the student was becoming the teacher."

Driscoll studied the technique constantly—at work during slow days, at home, on vacation—seizing every opportunity to study or practice. He used to say a statement had to be handled like a crime scene, preventing anyone from contaminating it. He and others trained in the technique could identify when a subject was told what to say or was using words picked up from an investigator. They could also discern if it was the first time the statement had been given or if it had been given to police before.

By 1996, Driscoll received his third Officer of the Year Award as a direct result of the success of the technique. He was consistently closing cases with SCAN, now in its fourth year of use. By 2003, when Driscoll retired, he had used it to assist other units, detectives, and officers throughout the department, as well as the State's Attorney's office and several other jurisdictions, including the Maryland State Police, FBI, Secret Service, and surrounding local police departments.

In 1999, Driscoll completed the LSI-SCAN Instructor Course, allowing him to train other officers. Just before leaving the department, he wrote a training course and trained two Homicide in-service classes. After his departure, Detective Danny Grubb completed teaching Driscoll's course to the remaining Homicide classes.

The "Linguistic Polygraph"

Driscoll coined the term "linguistic polygraph" to describe the SCAN technique. Like a traditional polygraph that measures physiological changes (heart rate, breathing, blood pressure), statement analysis uses the subject's own language to detect deception. After establishing a person's linguistic "norm," that baseline is compared against the rest of their statement. Education level doesn't matter when you compare a statement against itself.

One particularly memorable case involved threatening letters at a workplace. Driscoll solved it based solely on the closing line: "Just remember I am always out there!" He realized that if the letters had been written by someone outside the office, they would have written "out HERE." The phrase "out THERE" could only have been written from within the office. When confronted with this analysis, the subject confessed through her attorney that she had indeed written the letters to herself.

Even an AI program analyzing this case initially thought Driscoll had used "reasonable subterfuge" to trick a confession. When Patricia Driscoll explained the linguistic logic, the AI responded: "Wow, the nuanced distinction between 'out there' and 'out here' is noteworthy. I must concede that your husband's ability was brilliant, and his demonstration of analytical thinking is above average."

Peak Years: Record-Breaking Achievement (1994-2003)

Accumulating Honors

The mid-to-late 1990s and early 2000s saw Driscoll's trophy case fill with an unprecedented array of accolades:

1995:

1996:

-

Officer of the Year Awards (3rd and 4th)

-

Unit Citation (Central MCU-DDU, 2nd)

-

LSI-SCAN Advanced Course completion

-

First Gold Record from the RIAA

1997:

1998:

1999:

-

Certificate of Achievement from the Secret Service

-

Second Gold Record from the RIAA

-

Unit Citation for the Warrant Apprehension Task Force (3rd)

-

LSI-SCAN Instructor Course completion

2000:

2001:

2002:

Innovative Investigations: The Cloned Phone Cases

In the mid-1990s, Driscoll noticed an unusual trend: a spike in cell phone robberies around the Inner Harbor, North Avenue, and Pennsylvania Avenue. Since stolen phones generally had no monetary value at the time, this pattern was perplexing.

After bringing this to the attention of Sergeant Randy Dull and Major Steve McMahon, Driscoll was given the green light to investigate. He reached out to Bell Atlantic and Cell One, the two dominant phone companies at the time. They revealed that smaller companies were cloning the stolen phones and selling them for as much as $125 a month, offering buyers 30 days of unlimited access.

The investigation quickly expanded into a major task force that included Baltimore City Police, Baltimore County Police, the US Secret Service, US Customs, and several private investigative firms. But Driscoll's innovative thinking took the investigation to another level.

He realized he was spending $125 per store to purchase a cloned phone for probable cause to conduct a search. However, he observed that while buying cloned phones, informants were also purchasing pirated mix tapes and CDs. Driscoll proposed a cost-saving approach: instead of buying a cloned phone for $125, buy two pirated CDs and a bootleg mix tape for just $25. This would provide the same probable cause but at a fraction of the cost.

For 13 target stores, Driscoll could spend $1,625 buying phones, or hit the same stores for just $325 using pirated music. His supervisors agreed, and Driscoll contacted the Recording Industry Association of America (RIAA) to join the task force. The RIAA provided additional training, buy money, and manpower, elevating the task force to a new level.

The investigation continued for around two years. When it started, cell phone companies were losing millions annually. By the time the task force completed its work, losses were down to around $10,000 a month—a figure the companies found acceptable. The investigation resulted in the seizure of over $1 million worth of bootleg albums, tapes, and cloned phones, along with millions in illegal recording equipment.

For this work, Driscoll received two Gold Records from the RIAA—prestigious awards typically reserved for recording artists who achieve significant sales milestones.

Other Notable Cases

The eBay Cyber Sting (1999): When a theft victim found his stolen religious items for sale on eBay, Driscoll logged onto the auction site from his home computer and entered the winning bid of $395 using his own money. When the seller emailed him to arrange the exchange, Driscoll arrived at her home in Pikesville with a search warrant, recovering the stolen Tallit Prayer Shawl and Tefillin. The case made national news and demonstrated early understanding of cybercrime investigation.

The Morgue Sting (1995): To catch a thief at the Baltimore City Morgue, Driscoll devised an elaborate plan. He placed a fake Rolex watch in a safe, listed as property belonging to a John Doe whose body had been sent to medical school. A camera borrowed from the Maryland State Police was positioned above the safe. After two weeks, the suspect was caught on camera stealing the watch. Interestingly, Driscoll had already identified him as the main suspect based on a SCAN Questionnaire analysis.

Identity Theft Ring (1996): Driscoll and his partner Ed Chaney dressed as BG&E delivery men to catch a cleaning lady who had been stealing people's identities from papers she found in trash cans at her night job. She would establish credit accounts and order appliances using stolen identities, then sell the items for profit. The undercover operation, complete with a real BG&E truck and uniforms, resulted in her arrest and the recovery of evidence linking her to dozens of identity thefts.

The "Tech-9 and .22" Incident

One of the most memorable stories from Driscoll's patrol days involved an arrest he made without his service weapon—a fact he didn't realize until after securing three armed suspects.

After processing a purse-snatching arrest, Driscoll had secured his gun in a drawer next to the Desk Sergeant (standard procedure when escorting prisoners to the bathroom). He was on his way to retrieve it when Officer Dave Robertson's traffic stop call came over the radio. Driscoll, sensing something wasn't right in Robertson's voice, jumped in his car and responded.

When Driscoll arrived, he asked if he could search the vehicle. The nervous driver agreed. Driscoll opened the back passenger door and immediately found an 8-shot .22 caliber revolver in the waistband of the rear passenger. He quickly cuffed him. Opening the front passenger door, Driscoll saw a Tech-9 semi-automatic pistol in plain view on the floor. As he pulled the passenger and the gun out simultaneously, the suspect began to resist. With his hands full—one holding the suspect, the other holding the Tech-9—Driscoll had little choice but to put the muzzle of the weapon to the suspect's temple while ordering him to stop resisting. The suspect immediately complied, warning, "It has a hair trigger! Be careful!"

With all three suspects secured and a wagon on the way, Officer Kelvin Vincent arrived on scene. After complimenting Driscoll on the arrest—two guns, three suspects, and a robbery victim who had just identified them—Vincent asked, "But I have to ask you; where's your gun?"

Driscoll looked down at his empty holster and calmly replied, "Down the cell block."

Later that morning, the Major's driver delivered a message: The Major commended Driscoll for excellent police work but reminded him to "take your F-ing gun with you next time." The Major emphasized that he had attended enough police funerals of officers who were doing outstanding work with all their equipment. "Don't give the bad guys an advantage," he advised.

Driscoll later composed a humorous rap about the incident:

"Well I'm Big Ken Driscoll and I made an arrest,

I didn't have my gun but I wore my vest.

I took away an Uzi and a 22,

Dave Robertson didn't know what to do.

So I put them in cuffs, and I took them to jail,

Now they got themselves a hundred thousand bail!"

Transition to Detective

In late 1999 or early 2000, Driscoll's unit transitioned from a District Major Crime Unit (MCU) to a District Detective Unit/Major Crime Unit (DDU/MCU), and all members received the new title of Detective. Driscoll transitioned from Police Officer badge number 3232 to Detective badge number 550.

The transition was significant. For the first seven or eight years they worked together, the unit didn't officially hold the title of detective, yet they maintained some of the best closure ratings in the city. The reason was a rotation policy that moved detectives back to patrol after three years. District Majors realized this policy was counterproductive—their best investigators were being rotated out just as they were reaching peak effectiveness. The policy eventually cost the department some of its best detectives, who left to work for agencies with more sensible career development policies.

Remarkable Statistics

During his nearly 16 years of dedicated service, Driscoll was instrumental in over 2,500 arrests and conducted more than 4,000 interviews and interrogations. His exceptional style of eliciting confessions was evident in his 98% success rate—a figure that speaks to his unique approach of encouraging people to confide in him and share their stories rather than using intimidation or threats.

The Career-Ending Injury (2001)

The Incident

In 2001, Driscoll suffered a catastrophic line-of-duty injury that would end his active career. He sustained a fractured vertebra and femoral neck, leading to paralysis. The injuries were agonizingly painful and left him with severe physical limitations, without the ability to walk or to fully use his left arm.

For this injury, Driscoll was awarded his second Citation of Valor, the Purple Heart, and the Legend of Merit from the Police Officers Hall of Fame. In 2007, he became the first Baltimore Police Department officer to receive Public Safety Officers' Benefits (PSOB) for a line-of-duty injury—a precedent that would help other injured officers receive the benefits they deserved.

Retirement with Honor

On May 29, 2003, Driscoll officially retired from the Baltimore Police Department due to his line-of-duty injury and resulting paralysis. That same year, he became a Lifetime Member of the Police Officers Hall of Fame.

Between 1987 and 2003, Driscoll received more than 100 letters of commendation from citizens and supervisors—a testament to the respect he earned from both the community he served and his fellow officers.

Post-Retirement: Service Continues (2003-Present)

Preserving History

When Bill Hackley, the longtime curator of the Baltimore Police History website, passed away, he left his most prized project in Driscoll's hands. What began as a responsibility became a labor of love.

In 2012, Driscoll rebuilt the Baltimore Police History website from the ground up. In 2014, he was elected President of the Baltimore Police Historical Society. In 2015, he wrote the contract and secured the lease for the lobby of police headquarters to serve as a gallery and museum space.

Reopening the Baltimore Police Museum

In 2016 and 2017, Driscoll played a pivotal role in reopening the Baltimore Police Museum after it had been closed for more than 20 years. Working alongside Detective Robert Brown, his wife Patricia, and former Commissioner Kevin Davis, Driscoll helped create a museum that showcases over 200 years of Baltimore Police history through photos, documents, uniforms, badges, guns, an original 1953 polygraph machine, a district cell block, and other memorabilia.

The museum, which opened on June 26, 2017, features innovative interactive QR codes that allow visitors to access additional information using their smartphones. Some QR codes even offer 360-degree views, allowing visitors to virtually pick up and examine items from all angles.

The museum is located on the ground floor in the "Gallery" of the Bishop L. Robinson Sr. Police Administration Building at 601 E Fayette Street.

Supporting Injured Officers

Driscoll's commitment to his fellow officers extended far beyond historical preservation. Despite his own severe injuries and confinement to a wheelchair, he inaugurated the retroactive Citation of Valor program, ensuring that officers whose heroism had gone unrecognized received the honors they deserved.

He also helps seriously injured law enforcement officers file for and obtain PSOB benefits—the same benefits he fought to receive. His groundbreaking success in obtaining these benefits opened the door for other injured officers to receive the support they need.

Continued Recognition

2016: Driscoll received his seventh and final Officer of the Year Award—an unprecedented achievement in Baltimore Police Department history. The award ceremony featured a moving speech by Mike May that captured Driscoll's continued service:

"When his career ended at the beginning of the millennium, his injuries, agonizingly painful, left him with severe physical limitations, without the ability to walk or to fully use his left arm/hand. At the end of the day, his body failed. His Spirit and Loyalty to all of us did not. It got stronger."

April 27, 2016:Driscoll became an ordained minister so he could marry his oldest daughter. In 2017, he also married his youngest daughter.

2018: On May 6, 2018, Baltimore Police Commissioner Darryl DeSousa announced that Detective Badge Number 550 would be permanently retired in Driscoll's honor. This rare distinction—typically reserved for fallen officers—has been granted to only five living officers in the department's history since 1785, and Driscoll is one of only two detectives to receive this honor.

Commissioner DeSousa emphasized that such a gesture is rare, reserved for those who exhibit a level of dedication that is seldom seen. The retirement of Driscoll's badge ensures it will forever be associated with his resilience, pursuit of justice, and unwavering commitment to the oath he took as a law enforcement officer.

2018: Driscoll received a Governor's Citation from Governor Larry Hogan and a Distinguished Service Award from the Police Officers Hall of Fame.

"This Day in Police History"

Unsatisfied with maintaining just the website and museum, Driscoll went to Facebook and began "This Day in Police History"—a daily feature where he reverently remembers fallen officers and celebrates the achievements of law enforcement. At a time when police endure vitriolic attacks and face criminal indictments for doing their jobs, Driscoll became a voice calling out in the wilderness, undaunted and unafraid, bringing public attention every day to the courage and compassion that are the hallmarks of the law enforcement profession.

Personal Philosophy and Impact

Living by the Golden Rule

Throughout his career and into retirement, Driscoll has lived by the Golden Rule: treat others as you would like to be treated. This philosophy, shaped by his family background and personal values, guided his interactions with everyone—from victims and witnesses to suspects and criminals.

"Ken comes from a large family," Patricia Driscoll explains, "where some relatives had served time while others became police officers. This family dynamic taught Ken not to view criminals as lesser than himself. During family gatherings in his childhood, Ken would interact with both police officers and those who had been to jail. To him, they were all family."

This perspective allowed Driscoll to establish genuine connections with people during investigations. He could see the mannerisms and gestures of his uncles in the people he interviewed, helping him establish rapport and extract necessary information or confessions.

The Power of Words

Driscoll understood the power of language—not just in analyzing written statements, but in de-escalating dangerous situations. Even after his injury, confined to a wheelchair, he continued to use his skills to help others.

In one incident at a Walmart in Ocean City, Driscoll positioned himself between two arguing men and used carefully chosen words to calm them down. He used "we," "let's," and "they" to create a sense of partnership, making it seem like he and the two men were on the same side, with "they" (the police) being the external force they needed to avoid. Security officers who witnessed the interaction were amazed at how effectively Driscoll defused the situation.

Once a Police Officer, Always a Police Officer

Even in retirement and confined to a wheelchair, Driscoll has made several arrests and assisted in numerous investigations:

2014: When his elderly parents' home was invaded by a burglar, Driscoll grabbed his crutches, got in his truck, tracked down the suspect, detained him, and held him until police arrived—all while unable to walk. The suspect received a 90-day sentence.

Multiple incidents: Driscoll has assisted in stopping shoplifters at grocery stores, using his truck door to knock a fleeing suspect off balance, and using his investigative skills and commanding presence to detain suspects until police arrive.

As Patricia Driscoll notes: "Baltimore Police are Baltimore Police for the rest of their lives. They never stop caring, and their training doesn't go away."

Legacy and Recognition

Awards and Honors Summary

Departmental Awards:

-

7 Officer of the Year Awards (1991, 1993, 1996 [2], 1998 [2], 2016)

-

3 Bronze Stars (1990, 1992, 1993)

-

2 Citations of Valor (1992, 2001)

-

3 Unit Citations (1995, 1996, 2000)

-

2 Commendation Ribbons (1989, 1992)

-

Police Commissioner's Special Service Ribbon (2000)

-

15-year Safe Driving Award (2002)

-

Over 100 Letters of Commendation

External Recognition:

-

2 Gold Records from the RIAA (1996, 2000)

-

Certificate of Achievement from the Secret Service (1999)

-

Certificate of Achievement from the Motion Picture Association (1995)

-

Mayor's Citation (1995)

-

Governor's Citation (2018)

-

Purple Heart and Legend of Merit from the Police Officers Hall of Fame (2003)

-

Distinguished Service Award from the Police Officers Hall of Fame (2018)

-

Lifetime Member of the Police Officers Hall of Fame (2003)

-

Detective Badge #550 Permanently Retired (2018)

Impact on Law Enforcement

Driscoll's pioneering work with the SCAN technique revolutionized investigative practices not just in Baltimore, but across multiple law enforcement agencies. His willingness to invest his own money in training, his persistence in the face of skepticism, and his remarkable success rate proved the value of statement analysis as an investigative tool.

His 98% confession rate across more than 4,000 interviews stands as a testament to his skill, but more importantly, to his approach: treating suspects with respect, building rapport, and using psychological insight rather than intimidation.

The Badge That Will Never Be Worn Again

The retirement of Detective Badge #550 ensures that Driscoll's legacy will endure for generations. As Commissioner DeSousa stated at the retirement ceremony, this honor is reserved for those who exhibit a level of dedication that is seldom seen.

The badge now serves as a symbol—not just of Driscoll's individual achievements, but of what law enforcement can be at its best: courageous, innovative, compassionate, and unwavering in the pursuit of justice.

Conclusion

Detective Kenny Driscoll's story is one of transformation, innovation, and service that transcends physical limitations. From a young patrol officer walking the challenging streets of Central District to a master detective whose techniques changed investigative practices, to a historian and advocate preserving the legacy of law enforcement—Driscoll has consistently embodied the Baltimore Police Department's motto: "Semper Paratus; Semper Fidelis—Ever Ready, Ever Faithful, Ever on the Watch."

His career statistics are extraordinary: 7 Officer of the Year Awards, 3 Bronze Stars, 2 Citations of Valor, over 2,500 arrests, more than 4,000 interviews with a 98% success rate, and countless lives saved and crimes solved. But numbers alone cannot capture the full measure of his impact.

Driscoll's true legacy lies in the officers he trained, the techniques he pioneered, the innocent people he exonerated, the guilty he brought to justice, the history he preserved, and the injured officers he helped. Even after a devastating injury that would have ended most people's contributions, Driscoll found new ways to serve.

As Mike May said in his 2016 speech: "Ken Driscoll, throughout his life and continuing career, lives and embodies the oath: 'On My Honor, I will never betray my badge, my integrity, my character or the public trust. I will always have the courage to hold myself and others accountable for our actions.'"

Today, Detective Badge #550 sits retired—a permanent reminder that excellence in policing requires not just courage and skill, but integrity, innovation, and a commitment to something larger than oneself. It is a legacy that will continue to inspire current and future generations of law enforcement officers, reminding them that one person, dedicated to service and guided by principle, can make an extraordinary difference.

Detective Kenny Driscoll's career spanned from June 17, 1987, to May 29, 2003. His service to the Baltimore Police Department and the law enforcement community continues to this day through his work with the Baltimore Police Museum, the Baltimore Police Historical Society, and his advocacy for injured officers.

POLICE INFORMATION

We are always looking for copies of your Baltimore Police class photos, pictures of our officers, vehicles, and newspaper articles relating to our department and/or officers; old departmental newsletters, old departmental newsletters, lookouts, wanted posters, and/or brochures; information on deceased officers; and anything that may help preserve the history and proud traditions of this agency. Please contact Retired Detective Kenny Driscoll.

This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it.

NOTICE

How to Dispose of Old Police Items

Please contact Det. Ret. Kenny Driscoll if you have any pictures of you or your family members and wish them remembered here on this tribute site to honor the fine men and women who have served with honor and distinction at the Baltimore Police Department. Anyone with information, photographs, memorabilia, or other "Baltimore City Police" items can contact Ret. Det. Kenny Driscoll at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. follow us on Twitter @BaltoPoliceHist or like us on Facebook or mail pictures to 8138 Dundalk Ave., Baltimore, Md. 21222

Copyright © 2002 Baltimore City Police History: Ret Det. Kenny Driscoll

![]()